From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Urdu: محمد علی جناح ALA-LC: Muḥammad ʿAlī Jināḥ, born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a lawyer, politician, and the founder of Pakistan.[1] Jinnah served as leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until Pakistan's independenceon 14 August 1947, and then as Pakistan's first Governor-General from independence until his death. He is revered in Pakistan as Quaid-i-Azam(Urdu: قائد اعظم Great Leader) and Baba-i-Qaum (Urdu: بابائے قوم Father of the Nation). His birthday is observed as a national holiday.[2][3]

Born in Karachi and trained as a barrister at Lincoln's Inn in London, Jinnah rose to prominence in the Indian National Congress in the first two decades of the 20th century. In these early years of his political career, Jinnah advocated Hindu–Muslim unity, helping to shape the 1916 Lucknow Pact between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, in which Jinnah had also become prominent. Jinnah became a key leader in the All India Home Rule League, and proposed a fourteen-point constitutional reform plan to safeguard the political rights of Muslims. In 1920, however, Jinnah resigned from the Congress when it agreed to follow a campaign of satyagraha, or non-violent resistance, advocated by Mohandas Gandhi.

By 1940, Jinnah had come to believe that Indian Muslims should have their own state. In that year, the Muslim League, led by Jinnah, passed the Lahore Resolution, demanding a separate nation. During the Second World War, the League gained strength while leaders of the Congress were imprisoned, and in the elections held shortly after the war, it won most of the seats reserved for Muslims. Ultimately, the Congress and the Muslim League could not reach a power-sharing formula for a united India, leading all parties to agree to separate independence of a predominantly Hindu India, and for a Muslim-majority state, to be called Pakistan.

As the first Governor-General of Pakistan, Jinnah worked to establish the new nation's government and policies, and to aid the millions of Muslim migrants who had emigrated from the new nation of India to Pakistan afterindependence, personally supervising the establishment of refugee camps. Jinnah died at age 71 in September 1948, just over a year after Pakistan gained independence from the United Kingdom. He left a deep and respected legacy in Pakistan. According to his biographer, Stanley Wolpert, he remains Pakistan's greatest leader.

Background[edit]

Jinnah's given name at birth was Mahomedali Jinnahbhai,[a] and was born most likely in 1876,[b] to Jinnahbhai Poonja and his wife Mithibai, in a rented apartment on the second floor of Wazir Mansion, Karachi.[4] Jinnah's birthplace is in Sindh, a region today part of Pakistan, but then within the Bombay Presidency of British India. Jinnah's family was from a Gujarati,Khoja (shia) background, though Jinnah later followed the Twelver Shi'a teachings.[5] [6][7] Jinnah was from a middle-income background, his father was a merchant and was born to a family of weavers in the village of Paneli in the princely state ofGondal (Kathiawar, Gujarat); his mother was also of that village. They had moved to Karachi in 1875, having married before their departure. Karachi was then enjoying an economic boom: the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 meant it was 200 nautical miles closer to Europe for shipping than Bombay.[8][9] Jinnah was the second child;[10][11] he had three brothers and three sisters, including his younger sister Fatima Jinnah. The parents were native Gujarati speakers, and the children also came to speak Kutchi and English.[12] Except for Fatima, little is known of his siblings, where they settled or if they met with their brother as he advanced in his legal and political careers.[13]

As a boy, Jinnah lived for a time in Bombay with an aunt and may have attended the Gokal Das Tej Primary School there, later on studying at the Cathedral and John Connon School. In Karachi, he attended the Sindh-Madrasa-tul-Islam and theChristian Missionary Society High School.[14][15][16] He gained his matriculation from Bombay University at the high school. In his later years and especially after his death, a large number of stories about the boyhood of Pakistan's founder were circulated: that he spent all his spare time at the police court, listening to the proceedings, and that he studied his books by the glow of street lights for lack of other illumination. His official biographer, Hector Bolitho, writing in 1954, interviewed surviving boyhood associates, and obtained a tale that the young Jinnah discouraged other children from playing marbles in the dust, urging them to rise up, keep their hands and clothes clean, and play cricket instead.[17]

Governor-General[edit]

The Radcliffe Commission, dividing Bengal and Punjab, completed its work and reported to Mountbatten on 12 August; the last Viceroy held the maps until the 17th, not wanting to spoil the independence celebrations in both nations. There had already been ethnically charged violence and movement of populations; publication of the Radcliffe Line dividing the new nations sparked mass migration, murder, and ethnic cleansing. Many on the "wrong side" of the lines fled or were murdered, or murdered others, hoping to make facts on the ground which would reverse the commission's verdict. Radcliffe wrote in his report that he knew that neither side would be happy with his award; he declined his fee for the work.[170]Christopher Beaumont, Radcliffe's private secretary, later wrote that Mountbatten "must take the blame—though not the sole blame—for the massacres in the Punjab in which between 500,000 to a million men, women and children perished".[171] As many as 14,500,000 people relocated between India and Pakistan during and after partition.[171] Jinnah did what he could for the eight million people who migrated to Pakistan; although by now over 70 and frail from lung ailments, he travelled across West Pakistan and personally supervised the provision of aid.[172] According to Ahmed, "What Pakistan needed desperately in those early months was a symbol of the state, one that would unify people and give them the courage and resolve to succeed."[173]

Jinnah had a troublesome ordeal with NWFP. The referendum of NWFP July 1947, whether to be a part of Pakistan orIndia, had been tainted with low electoral turnout as less than 10% of the total population were allowed to partake in the referendum.[174] On 22 August 1947, just after a week of becoming governor general Jinnah dissolved the elected government of Dr. Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan.[175] Later on, Abdul Qayyum Khan was put in place by Jinnah in the Pukhtoon dominated province despite him being a Kashmiri.[176][177] On 12 August 1948 the Babrra massacre in Charsadda was ordered resulting in the death of 400 people aligned with the Khudai Khidmatgar movement.[178]

Along with Liaquat and Abdur Rab Nishtar, Jinnah represented Pakistan's interests in the Division Council to appropriately divide public assets between India and Pakistan.[179] Pakistan was supposed to receive one-sixth of the pre-independence government's assets, carefully divided by agreement, even specifying how many sheets of paper each side would receive. The new Indian state, however, was slow to deliver, hoping for the collapse of the nascent Pakistani government, and reunion. Few members of the Indian Civil Service and the Indian Police Service had chosen Pakistan, resulting in staff shortages. Crop growers found their markets on the other side of an international border. There were shortages of machinery, not all of which was made in Pakistan. In addition to the massive refugee problem, the new government sought to save abandoned crops, establish security in a chaotic situation, and provide basic services. According to economist Yasmeen Niaz Mohiuddin in her study of Pakistan, "although Pakistan was born in bloodshed and turmoil, it survived in the initial and difficult months after partition only because of the tremendous sacrifices made by its people and the selfless efforts of its great leader."[180]

The Indian Princely States, of which there were several hundred, were advised by the departing British to choose whether to join Pakistan or India. Most did so prior to independence, but the holdouts contributed to what have become lasting divisions between the two nations.[181] Indian leaders were angered at Jinnah's courting the princes of Jodhpur, Bhopal andIndore to accede to Pakistan—these princely states did not border Pakistan, and each had a Hindu-majority population.[182]The coastal princely state of Junagadh, which had a majority-Hindu population, did accede to Pakistan in September 1947, with its ruler's dewan, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, personally delivering the accession papers to Jinnah. The Indian army occupied the principality in November, forcing its former leaders, including Bhutto, to flee to Pakistan, beginning the politically powerful Bhutto family.[183]

The most contentious of the disputes was, and continues to be, that over the princely state of Kashmir. It had a Muslim-majority population and a Hindu maharaja, Sir Hari Singh, who stalled his decision on which nation to join. With the population in revolt in October 1947, aided by Pakistani irregulars, the maharaja acceded to India; Indian troops were airlifted in. Jinnah objected to this action, and ordered that Pakistani troops move into Kashmir. The Pakistani Army was still commanded by British officers, and the commanding officer, General Sir Douglas Gracey, refused the order, stating that he would not move into what he considered the territory of another nation without approval from higher authority, which was not forthcoming. Jinnah withdrew the order. This did not stop the violence there, which has broken into war between India and Pakistan from time to time since.[181][184]

Some historians allege that Jinnah's courting the rulers of Hindu-majority states and his gambit with Junagadh are evidence of ill-intent towards India, as Jinnah had promoted separation by religion, yet tried to gain the accession of Hindu-majority states.[185] In his book Patel: A Life, Rajmohan Gandhi asserts that Jinnah hoped for a plebiscite in Junagadh, knowing Pakistan would lose, in the hope the principle would be established for Kashmir.[186] Despite the United Nations Security Council Resolution 47 issued at India's request for a plebiscite in Kashmir after the withdrawal of Pakistani forces, this has never occurred.[184]

In January 1948, the Indian government finally agreed to pay Pakistan its share of British India's assets. They were impelled by Gandhi, who threatened a fast until death. Only days later, Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, who believed that Gandhi was pro-Muslim. Jinnah made a brief statement of condolence, calling Gandhi "one of the greatest men produced by the Hindu community".[187]

In a radio talk addressed to the people of USA broadcast in February 1948, Jinnah said:

In March, Jinnah, despite his declining health, made his only post-independence visit to East Pakistan. In a speech before a crowd estimated at 300,000, Jinnah stated (in English) that Urdu alone should be the national language, believing a single language was needed for a nation to remain united. The Bengali-speaking people of East Pakistan strongly opposed this policy, and in 1971 the official language issue was a factor in the region's secession to form Bangladesh.[188]

After the establishment of Pakistan, Pakistani currency notes had the image of George V printed on them. These notes were in circulation till 30 June 1949. But on 1 April 1949, these notes were stamped with "Government of Pakistan" and were used as legal tenders. On the same day, the then Finance Minister of Pakistan, Malik Ghulam Muhammad, presented a new set of seven coins (Re. 1, ₨. 1⁄2, ₨. 1⁄4, A. 2, A. 1, A. 1⁄2 and Pe. 1) to Jinnah in the Governor House and were issued as the first coins minted by the Government of Pakistan.

Quaid-e-Azam[edit]

Quaid-e-Azam (The Great Leader) is the title of Jinnah the Pakistan's first Governor-General from independence until his death. This is an honorific title given to a man considered the driving force behind the establishment of his country, state, or nation. Jinnah's other title is Baba-i-Qaum (Father of the Nation). His birthday is observed as a national holiday.[189][190] [191]The title Quaid-e Azam was given to Jinnah at first by Mian Ferozuddin Ahmed that became an official title on 11 August 1947, with the resolution of Liaquat Ali Khan in the Pakistan Constituent Assembly. There are some sources that endorse that Gandhi gave him that title.[192]

Illness and death[edit]

From the 1930s, Jinnah suffered from tuberculosis; only his sister and a few others close to him were aware of his condition. Jinnah believed public knowledge of his lung ailments would hurt him politically. In a 1938 letter, he wrote to a supporter that "you must have read in the papers how during my tours ... I suffered, which was not because there was anything wrong with me, but the irregularities [of the schedule] and over-strain told upon my health".[193][194] Many years later, Mountbatten stated that if he had known Jinnah was so physically ill, he would have stalled, hoping Jinnah's death would avert partition.[195] Fatima Jinnah later wrote, "even in his hour of triumph, the Quaid-e-Azam was gravely ill ... He worked in a frenzy to consolidate Pakistan. And, of course, he totally neglected his health ..."[196] Jinnah worked with a tin of Craven "A" cigarettes at his desk, of which he had smoked 50 or more a day for the previous 30 years, as well as a box of Cuban cigars. As his health got worse, he took longer and longer rest breaks in the private wing of Government House in Karachi, where only he, Fatima and the servants were allowed.[197]

In June 1948, he and Fatima flew to Quetta, in the mountains of Baluchistan, where the weather was cooler than in Karachi. He could not completely rest there, addressing the officers at the Command and Staff College saying, "you, along with the other Forces of Pakistan, are the custodians of the life, property and honour of the people of Pakistan."[198] He returned to Karachi for the 1 July opening ceremony for the State Bank of Pakistan, at which he spoke. A reception by the Canadian trade commissioner that evening in honour of Dominion Day was the last public event he attended.[199]

On 6 July 1948, Jinnah returned to Quetta, but at the advice of doctors, soon journeyed to an even higher retreat at Ziarat. Jinnah had always been reluctant to undergo medical treatment, but realising his condition was getting worse, the Pakistani government sent the best doctors it could find to treat him. Tests confirmed tuberculosis, and also showed evidence of advanced lung cancer. Jinnah was informed and asked for full information on his disease and for care in how his sister was told. He was treated with the new "miracle drug" of streptomycin, but it did not help. Jinnah's condition continued to deteriorate despite the Eid prayers of his people. He was moved to the lower altitude of Quetta on 13 August, the eve ofIndependence Day, for which a statement ghost-written for him was released. Despite an increase in appetite (he then weighed just over 36 kilograms [79 lb]), it was clear to his doctors that if he was to return to Karachi in life, he would have to do so very soon. Jinnah, however, was reluctant to go, not wishing his aides to see him as an invalid on a stretcher.[200]

By 9 September, Jinnah had also developed pneumonia. Doctors urged him to return to Karachi, where he could receive better care, and with his agreement, he was flown there on 11 September. Dr. Ilahi Bux, his personal physician, believed that Jinnah's change of mind was caused by foreknowledge of death. The plane landed at Karachi that afternoon, to be met by Jinnah's limousine, and an ambulance into which Jinnah's stretcher was placed. The ambulance broke down on the road into town, and the Governor-General and those with him waited for another to arrive; he could not be placed in the car as he could not sit up. They waited by the roadside in oppressive heat as trucks and buses passed by, unsuitable for transporting the dying man and with their occupants not knowing of Jinnah's presence. After an hour, the replacement ambulance came, and transported Jinnah to Government House, arriving there over two hours after the landing. Jinnah died at 10:20 pm at his home in Karachi on 11 September 1948 at the age of 71, just over a year after Pakistan's creation.[201][202]

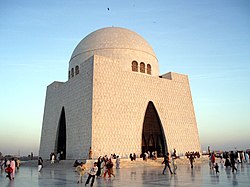

Indian Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru stated upon Jinnah's death, "How shall we judge him? I have been very angry with him often during the past years. But now there is no bitterness in my thought of him, only a great sadness for all that has been ... he succeeded in his quest and gained his objective, but at what a cost and with what a difference from what he had imagined."[203] Jinnah was buried on 12 September 1948 amid official mourning in both India and Pakistan; a million people gathered for his funeral. Indian Governor-General Rajagopalachari cancelled an official reception that day in honour of the late leader. Today, Jinnah rests in a large marble mausoleum, Mazar-e-Quaid, in Karachi.[204][205][206]

Aftermath[edit]

Dina Wadia, Jinnah's daughter, remained in India after independence before ultimately settling in New York City. In the 1965 presidential election, Fatima Jinnah, by then known as Madar-e-Millat ("Mother of the Nation"), became the presidential candidate of a coalition of political parties that opposed the rule of President Ayub Khan, but was not successful.[207]

The Jinnah House in Malabar Hill, Bombay, is in the possession of the Government of India, but the issue of its ownership has been disputed by the Government of Pakistan.[208] Jinnah had personally requested Prime Minister Nehru to preserve the house, hoping one day he could return to Mumbai. There are proposals for the house be offered to the government of Pakistan to establish a consulate in the city as a goodwill gesture, but Dina Wadia has also asked for the property.[208][209]

After Jinnah died, his sister Fatima asked the court to execute Jinnah's will under Shia Islamic law.[210] This subsequently became the part of the argument in Pakistan about Jinnah's religious affiliation. Vali Nasr says Jinnah "was an Ismaili by birth and a Twelver Shia by confession, though not a religiously observant man."[211] In a 1970 legal challenge, Hussain Ali Ganji Walji claimed Jinnah had converted to Sunni Islam, but the High Court rejected this claim in 1976, effectively accepting the Jinnah family as Shia.[212] According to the journalist Khaled Ahmed, Jinnah publicly had a non-sectarian stance and "was at pains to gather the Muslims of India under the banner of a general Muslim faith and not under a divisive sectarian identity." Ahemd reports a 1970 Pakistani court decision stating that Jinnah's "secular Muslim faith made him neither Shia nor Sunni", and one from 1984 maintaining that "the Quaid was definitely not a Shia". Liaquat H. Merchant, Jinnah's grandnephew, elaborates that "he was also not a Sunni, he was simply a Muslim".[210]

Legacy and historical view[edit]

Jinnah's legacy is Pakistan. According to Mohiuddin, "He was and continues to be as highly honored in Pakistan as [first US president] George Washington is in the United States ... Pakistan owes its very existence to his drive, tenacity, and judgment ... Jinnah's importance in the creation of Pakistan was monumental and immeasurable."[213] Stanley Wolpert, giving a speech in honour of Jinnah in 1998, deemed him Pakistan's greatest leader.[214]

According to Singh, "With Jinnah's death Pakistan lost its moorings. In India there will not easily arrive another Gandhi, nor in Pakistan another Jinnah."[215]Malik writes, "As long as Jinnah was alive, he could persuade and even pressure regional leaders toward greater mutual accommodation, but after his death, the lack of consensus on the distribution of political power and economic resources often turned controversial."[216] According to Mohiuddin, "Jinnah's death deprived Pakistan of a leader who could have enhanced stability and democratic governance ... The rocky road to democracy in Pakistan and the relatively smooth one in India can in some measure be ascribed to Pakistan's tragedy of losing an incorruptible and highly revered leader so soon after independence."[217]

Jinnah is depicted on all Pakistani rupee currency, and is the namesake of many Pakistani public institutions. The former Quaid-i-Azam International Airport in Karachi, now called the Jinnah International Airport, is Pakistan's busiest. One of the largest streets in the Turkish capital Ankara, Cinnah Caddesi, is named after him, as is the Mohammad Ali Jenah Expressway in Tehran, Iran. The royalist government of Iran also released a stamp commemorating the centennial of Jinnah's birth in 1976. In Chicago, a portion of Devon Avenue was named "Mohammed Ali Jinnah Way". The Mazar-e-Quaid, Jinnah's mausoleum, is among Karachi's landmarks.[218] The "Jinnah Tower" in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India, was built to commemorate Jinnah.[219]

There is a considerable amount of scholarship on Jinnah which stems from Pakistan; according to Akbar S. Ahmed, it is not widely read outside the country and usually avoids even the slightest criticism of Jinnah.[220] According to Ahmed, nearly every book about Jinnah outside Pakistan mentions that he drank alcohol, but this is omitted from books inside Pakistan. Ahmed suggests that depicting the Quaid drinking alcohol would weaken Jinnah's Islamic identity, and by extension, Pakistan's. Some sources allege he gave up alcohol near the end of his life.[99][221]

According to historian Ayesha Jalal, while there is a tendency towards hagiography in the Pakistani view of Jinnah, in India he is viewed negatively.[222] Ahmed deems Jinnah "the most maligned person in recent Indian history ... In India, many see him as the demon who divided the land."[223] Even many Indian Muslims see Jinnah negatively, blaming him for their woes as a minority in that state.[224] Some historians such as Jalal and H. M. Seervai assert that Jinnah never wanted the partition of India—it was the outcome of the Congress leaders being unwilling to share power with the Muslim League. They contend that Jinnah only used the Pakistan demand in an attempt to mobilise support to obtain significant political rights for Muslims.[225] Jinnah has gained the admiration of Indian nationalist politicians such as Lal Krishna Advani, whose comments praising Jinnah caused an uproar in his Bharatiya Janata Party.[226]

The view of Jinnah in the West has been shaped to some extent by his portrayal in Sir Richard Attenborough's 1982 film,Gandhi. The film was dedicated to Nehru and Mountbatten and was given considerable support by Nehru's daughter, the Indian prime minister, Indira Gandhi. It portrays Jinnah (played by Alyque Padamsee) in an unflattering light, who seems to act out of jealousy of Gandhi. Padamsee later stated that his portrayal was not historically accurate.[227]

In a journal article on Pakistan's first governor-general, historian R. J. Moore wrote that Jinnah is universally recognised as central to the creation of Pakistan.[228] Wolpert summarises the profound effect that Jinnah had on the world:

No comments:

Post a Comment